hinkey of yale

by Hugh Fullerton. Liberty Magazine, January 27, 1926

Hinkey of Yale is dead.

The oddest, shyest, most saturnine, perhaps the most misunderstood and certainly one of the bravest figures of the athletic world, the greatest football end of all time, the man who, according to Yale tradition, never permitted a runner to gain ground around his end in four seasons, finally allowed Death to score.

Late in the evening of December 29, from his bed in a sanitarium at Southern Pines, North Carolina, Hinkey wrote a telegram to George T. Adee of New York, who back in the brave days played quarterback on his teams, and said:

“Charon is at the crossing.”

Just twelve hours later Hinkey’s clutch, which had held death off through twelve years, slipped and the grim reaper fell on him.

Hinkey was one of the queerest personalities in the history of athletics. Probably the most hated and abused player that ever lived – and the most adored and beloved by those who knew him best. He never took the trouble to explain, to apologize, or to contradict charges. A hero, probably the greatest Yale ever had, he wandered through the campus singularly alone, avoiding those who tried to admire him, repulsing those who would have been his chums. He was known only to those who fought for years alongside him in the most desperate football games in history. He had fewer friends than the newest freshmen. The few who managed to break through the crust of hardness under which he hid a sensitive and proud spirit loved him as few men have been loved and clung to him until the end, through a life marred by illness and disappointments.

Just a few weeks before his death Frank Butterworth, who played alongside him in many games, and George Adee, who for four years played quarterback, went down to Southern Pines to see him. He was in bed, where for two and a half years he had battled tuberculosis.

As they were gripping his hand in farewell they knew the chances were they never would meet again. The men who had battled through the bloodiest and fiercest games of football history, who had clung together and treasured the memory of college days, choked up as they tried to smile. Hinkey’s veneer of hardness cracked. His voice grew huskier, and suddenly tears welled out from his eyes and rolled down his cheeks. He gulped as he dashed away the tears and said:

“Damn that medicine. It’s full of dope and makes my eyes water.”

That was Hinkey; the saturnine, the desperate, the cold-blooded; the man whose playing caused the editorial writer of the New York Post back in 1894 to write:

“No father or mother worthy the name would permit a son to associate with the set of Yale brutes on Hinkey’s football team.”

It is rather hard to reconstruct a character such as Frank Hinkey, because at Yale, and through the other colleges, traditions, most of them untrue, have grown up around him. One pictures him as murderous, merciless, brutal; another as shy, disliking praise, avoiding publicity, but loyal and devoted to his friends.

Hinkey remained always a sort of man of mystery.

It was in 1889 that a light, wiry, quiet little fellow went to Andover to enter the great preparatory school. He hailed from Tonawanda, New York. He weighed about 125 pounds, looked slight and unfit for a game as rough as the football of that day. When the call came for candidates for the first-year team the boy appeared in a makeshift uniform, was sent to an end position, and suddenly metamorphosed from a silent, almost shrinking “new kid” to a fighting, determined, fierce-tackling bundle of nerves and muscles.

His fame spread beyond the prep-school limits, and when in 1891 Yale was preparing its team for the season the news that Hinkey of Andover would join the squad filled the coaches with joy. The coaching system of those days was different from that of today.

Walter Camp was head of the system and twenty or more old players returned each fall to work with the players in each position. There were Billy Rhoades, ’91; Ray Tompkins, ’84; Dr. John A. Hartwell, ’89, Shef, who came back to take medicine, Kit Wallace, ’89; Howard Knapp, McClung, Vance McCormick – heroes of the moleskins of previous years, who considered it part of their duty to help Yale.

One day there appearead on the field a light fellow who held back and seemed to hesitate about approaching the coaches. He seemed so light and inoffensive the coaches hesitated whether to let him keep a uniform. He went to end and McClung, who was heavy, fast, and Yale’s most powerful plunger, started around that end. There was a snakelike dart, a pair of cast-steel arms gripped McClung’s legs, and he was thrown backward toward his own goal. He tried again and again – and each time that pair of unavoidable arms came through the interference and dragged the great Yale captain down.

McClung was not only jarred but impressed. Before the practice ended there was no doubt that Hinkey, who then weighed 135 pounds, had made the team. Probably no candidate for a football team ever made it quite as thoroughly as Frank Hinkey did. He not only won a regular position at end, but he won both positions. Crosby and Josh Hartwell were the veteran ends. Hinkey not only won the position from Crosby but he forced Hartwell from left end to right and assumed the leadership of both attack and defense.

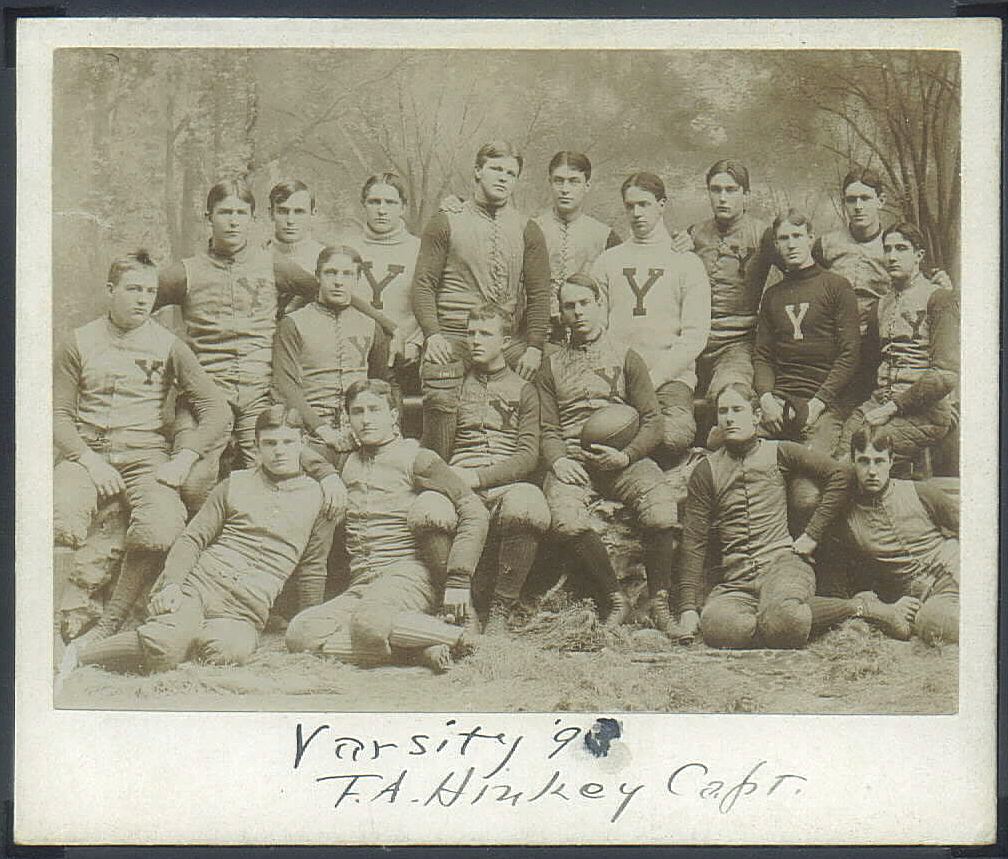

1893 Yale Football Team (John Spano Collection)

The four years of Hinkey’s reign in football are the most glorious in Yale’s football history – years filled with desperate conflicts and bitter controversies, all centering around Hinkey, the silent. He played on the teams of 1891-92-93-94, and was All-American end on Camp’s team all four years. No man and no team ever achieved the feats of Hinkey’s teams. In four years Yale scored 1606 points to its opponents’ 26. The team scored on six times; Princeton, Harvard, and Pennsylvania each scored a touchdown; Army, Brown, and Harvard each scored by kicks. Only one game in all that time did Yale lose: that in 1893 when Hinkey’s team was beaten by Princeton 6 to 0.

In that game Hinkey, who according to Yale tradition never was hurt, had been kicked in the head and played through in dazed condition and not until long after the final whistle blew did he know his team had met defeat.

Those were the days of the giants at New Haven, giants in stature led by one of the lightest of the team. There were great players in the four years. His first year as a freshman, Hinkey played with the giant Pudge Heffelfinger and Yale coaches even today cannot decide whether Heffelfinger, Hinkey, or (Ted) Coy was Yale’s greatest football hero. McClung, Winter, Wallace, the late Colonel Greenway, Vance McCormick, Stillman, Brinck Thorne, Frank Butterworth, George Adee, a dozen other great stars, played, with always the little, fighting, grim-faced Hinkey as the soul and spirit of the team.

In 1891 Yale scored 491 points to 0 for the opponents; in 1892, 368 points to 0; in 1893, 326 to 12, and in Hinkey’s final year, 421 to 14. Hinkey was captain in 1893 and 1894, playing outside the giant Beard, who weighed 210 pounds.

A hard driver, fierce and impatient, Hinkey tried every way to prevent Beard from crashing into interference and putting himself out of the plays, and finally, irritated, he deliberately kicked the 210-pound tackle as he stooped over and threatened to kick him off the field.

Modern football fans, perhaps, cannot appreciate the fierceness and the viciousness of football in those days. Yale played twelve or more games a year; in 1894 the team played fourteen games and, save one or two light practice games, Hinkey was in every game – and almost in every scrimmage. It was the day of battering-line plunging, mass-formation plays, and how a man who, at his best, weighed but 144 pounds could stand the hammering and could meet and overthrow men of over 200 is hard to understand. Yet Hinkey never was out of a game through injuries, and it is tradition that he never tackled a runner without throwing him back toward his own goal.

When he became captain the growing hatred of Yale among the beaten colleges increased and was centered upon the silent, taciturn fellow who, in action, looked like a fiend, and whose fierce tackles broke the spirit of other teams.

Yet every man who played under Hinkey knows that, brief as his talks to the team were, they always ended: “If you can’t win by fair means – don’t win at all- but you’ve got to win.”

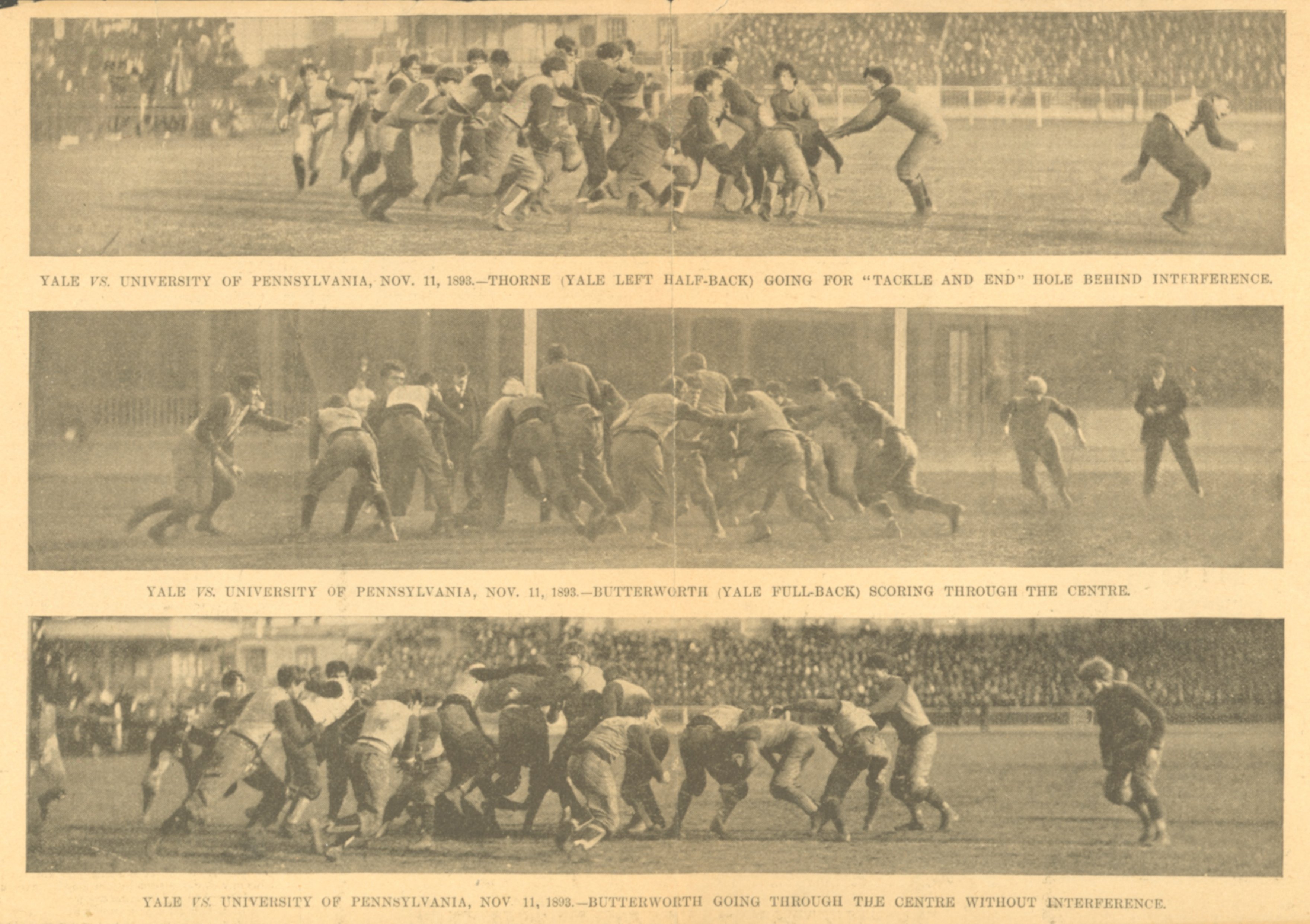

At that time, unfortunately, several newspapers were engaged in a crusade against football, charging that it was murderous, brutal, and dangerous. Hinkey’s name became a synonym for vicious football. There were two games played during those four years that will go down in history, the game between Yale and Pennsylvania played in New York in 1893, and the game between Yale and Harvard played at Springfield in 1894.

The Pennsylvania game came near destroying football. Perhaps never have two teams fought as desperately or as mercilessly. Penn had a powerful, determined team, primed to beat Hinkey’s unbeatable eleven. It happened that a football genius had arisen at Harvard, a man who was not a player. His name was Deland; Lorin Deland, who had added to his fame by becoming the husband of Margaret Deland, the writer. He invented the flying wedge, which became the man-trampling play of football. It was a combination of pile driver and buffalo herd stampede. Harvard had used it against Yale from the kickoff, and although he never had seen it before, Hinkey solved the play after seeing it twice.

“Don’t crash into it, let the interference go past,” he ordered, and Yale, letting the Harvard interference sweep past, tore in from behind and stopped the play.

The play invented by Deland was improved upon by this great Pennsylvania team, which commenced forming the flying wedge from line of scrimmage, by dropping linesmen back to form a wedge with the backs and massing against an end or tackle.

There was bitter feeling, much talk and boasting prior to the meeting of Penn and Yale in New York. Suddenly Penn cut loose its flying wedge and sent the play again and again over the Yale ends and tackles, crushing them. Hinkey had solved the play and was screaming orders for his men to let the interference pass and get the man. But in five plays Penn carried the ball over Yale’s line and the crowd went wild, thinking at last Yale was beaten. Hinkey was raving, threatening his own men, screaming orders, and suddenly Yale braced and commenced the fiercest fight of the year. From that on the game was a slaughter. Perhaps no more vicious struggle ever was seen on a gridiron.

Officials were almost helpless. Neither side gave nor asked quarter, but fought to exhaustion or until removed from the game because of injuries. The stretcher-bearers were busy – and the Yale team emerged from the combat victors, but terribly crippled.

The New York World’s description of that game would make good reading for moderns. The World was then engaged in proving the game to be brutal – and according to the description one would imagine the officials had to call time while ground-keepers dipped up buckets of blood and the surgeons worked at amputations on the side-lines.

Exaggerated as the accounts were, there is no doubt that the game was the fiercest fought in modern times, and of the sixteen injured, eleven were Yale men. Penn lost the game, but was six up on serious injuries, according to the accounts. This is not counting Frank Butterworth, who emerged with teeth marks in his back where a Penn player had tried to bite a steak out of him.

The game caused such bitterness that Yale severed athletic relations with Penn and never played them again until last fall (article was written in 1926).

The Yale-Harvard game of 1894 – the climax of Hinkey’s great career – was another desperate struggle. During that fierce fight Wrightington of Harvard suffered a broken collar bone and Harvard charged that Frank Hinkey had purposely broken the bone to weaken the Crimson team. The truth of the matter is that Louis Hinkey, Frank’s brother, had broken through and downed Wrightington, tackling him about the knees. The Harvard player attempted to shake loose and crawl forward and the giant Beard dropped with his knees in front to stop the crawl, and broke the Harvard man’s collar bone.

Hinkey made no denial of the accusation, but Yale was so wrought up over the persistent charges against Hinkey that it demanded a withdrawal of the charge and a formal apology from Harvard. This Harvard refused to do- athletic relations were broken off and for two years Yale refused to play Harvard.

So great was the feeling against Hinkey outside of Yale and so great the adoration of his fellows that Yale alumni decided to recognize the situation, and toward the end of his college career a great banquet was given his honor as a testimonial of the belief of Yale men that the charges were untrue. At that banquet player after player, every man who had played with Hinkey in the four years, arose and declared they never had seen Hinkey do a mean or unsportsmanlike thing on the football field.

Sheppard Homans, Princeton’s famous “Shep,” counted one of the greatest fullbacks of his day, now a resident of Englewood, N.J., played against Frank Hinkey twice. He was asked how Hinkey tackled.

“Like a fiend,” he said. “I don’t remember any particular tackle he made on me. Poe and I had a play around end and I remember we never got past Hinkey either in 1891 or 1892. He came low, and hard, with arms stretched out, and the next thing a fellow knew he was past the interference, grabbed you low, and stopped you in your tracks or threw you backward.”

“He tackled clean, played clean. Princeton never had a complaint against him. I believe he and Poe were the hardest tacklers the game ever knew.”

Hinkey was graduated with average standing and during his entire college career never was in scholastic troubles. Neither did he seek high standing. After graduation he went West and was superintendent of a smelter in Iowa. His health, never robust, was threatened, and the beginning of tuberculosis was evident.

In 1914, when Yale’s football prestige was threatened, Hinkey was summoned back to coach the teams. Instead of being out of date Hinkey was still years ahead of Eastern football.

He who was largely responsible for the use of the lateral pass had seen the pass used in the West and came back determined to bring Yale up to date. He revolutionized Yale football methods and strove to teach the modern game.

The first year he was fairly successful, but the resentment of the Old Guard and the Down Town Athletic Association against modern football was so bitter that before the next year he was undermined until his task was a hopeless one.

Frank Hinkey circa 1918

He finally settled in a little Illinois village called Morrisonville, where he had found his bride. Nearly three years ago his health failed utterly, and tuberculosis seized upon him. The fact is he had the disease for a long time, and kept silent. Finally he went to Southern Pines to a sanitarium and commenced the long fight to get well. There were times when he seemed to have the battle won. He kept the fact of his illness secret, but some of his closest friends learned of his condition and sought him out.

Frank Butterworth, Yale hero who played with him; George Adee, who served beside him for four years; Walter (Dutch) Carter, Yale’s great pitcher, who roomed with him at Yale, and others knew of it and that his case was hopeless.

There is something beautiful in the friendships formed in the college days and among men who had fought together for a cause. The old mates kept the secret well, but frequently by ones or twos they would journey down into North Carolina to spend a day or two trying to cheer Hinkey.

Shortly before last Christmas Adee and Butterworth made a trip to Southern Pines and spent the day with Hinkey, talking over the brave days when they wore the moleskins and the blue of Yale, and told Hinkey about the team in its fortunes.

They had tickets and reservations to go with a party and see him again early in January, and then just at the end of the year came the telegram:

“Charon is at the crossing.”

And lying beside it was another telegram from the doctor saying: “Hinkey died this morning.”

So Hinkey of Yale, with Charon at the bow, crossed the dark river to a land where his brave, shy spirit will be understood, and where it will be recorded that he fought a hard and a fair fight.