Frank hinkey's end play

Yale Alumni Weekly. Jan 7, 1927

The New York Sun recently published an article on Frank Hinkey, '95, by George Trevor, from which the following terrifying excerpts are taken - and to those who remember Hinkey in action, they sound true:

In the days when Hinkey's name struck the iron of fear deep into Harvard souls, an old time Harvard player of the eighties sauntered onto Yale Field and asked the Eli coach to point out the Blue celebrities. The Crimson grad was properly impressed by the generous girth of "Pudge" Heffelfinger, the rugged massiveness of Foster Sanford, and the imposing figure of Lee "Bum" McClung. "Where's this Frank Hinkey I hear so much about?" queried the cantab. Hinkey was identified. The Bostonian was incredulous. "Harvard frightened by that little shrimp!" he said, "I'm ashamed of Harvard".

Aptly they called Hinkey "the living flame." Like a disembodied spirit, he drifted through interference to nail the man with the ball. Hinkey didn't have to be taught football. He was an instinctive player - a genius who came naturally by the original, orthodox technic of tackling which defied imitation. Although he rarely weighed over 145 pounds in good condition, Hinkey's equal as a savage tackler has yet to don moleskins. When Frank hit them - "they stayed hit." There was something awe inspiring about the way his victims lay motionless on the turf, unable to rise. The shock effect of Hinkey's tackling stunned the runner, just as a blast of dynamite produces a concussion in sea water, paralyzing every fish within a given radius.

No wonder Hinkey got an underserved reputation as a dirty player! Rival partisans couldn't understand how such a frail scrawny, cadaverous little chap could knock giant opponents kicking by the force of his tackles unless he resorted to illegal methods. As a matter of fact, Hinkey never knowingly violated the code of sportsmanship. He scorned dirty tactics. He indulged in none of the questionable tricks which were common practice in the savage football of a rougher, more virile era. Yet nine times out of ten Hinkey got the blame for any crude stuff which happened to be pulled in the thick of the scrimmage. For all the good it did him, Hinkey might just as well have overstepped the boundaries of clean play.

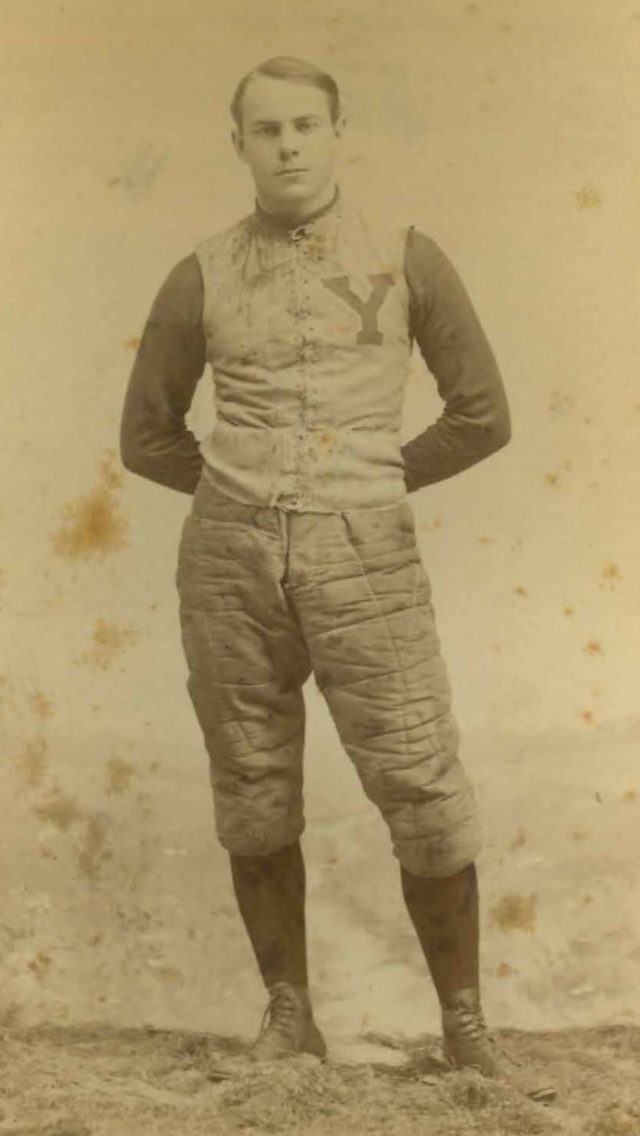

Frank Hinkey circa 1893 (Hinkey Archive)

But why Hinkey? The answer to that riddle leads one into the realms of physiology and psychology. Hinkey was abnormal in physical build and in psychic processes. The secret of his terrific tackling lay in the fact that he could fold up like an accordion when he crouched down in the line; his bobbing head, weaving from side to side like a cobra's, seemed to be scraping the turf. Hinkey's 145 pounds were solid bone, sinew and muscle. His body felt like tempered steel to the touch. He resembled a tightly coiled watch spring - which, when released, expanded with explosive force.

It was Hinkey's uncanny ability "to collapse" - to fold up like a stack of cards - that gave him his dreaded reputation as a tackler. Get this! Hinkey did not storm impetuously at his man, like that swashbuckling, swaggering terror - Tom Shelvin. On the contrary, Hinkey stalked his human quarry as stealthily as a jaguar shadows its prey. Hinkey "stole into" the runner, instead of rushing at hime. As quick as a panther's paw those scrawny, steel thewed arms shot out. With the cunning of a jiu-jitsu wrestler, Hinkey secured his hold. Then with a snap like the crack of a lash, he whip-sawed his hapless rival across his shoulder. Nothing like Hinkey's tackling exists today. He made the runner do half the work. That was the artifice of Hinkey's technic. The carrier literally "picked himself up," Hinkey's body providing the fulcrum. All Frank had to do was crack the whip.

Hinkey "cracked 'em in two." His victims were frequently stunned for a minute or more, yet Frank's tackles were clean and fair. It was his brother, Louis Hinkey, who was responsible for Edgar Wrightington's broken collar bone in the famous Yale-Harvard game of 1894 at Springfield. Wrightington's injury was purely accidental but Frank Hinkey was accused by hot heads of deliberately jumping on the Crimson runner. Frank was actually fifteen yards away from the play, according to Jim Rodgers, the Eli tackle. "The silent one," however, quietly took the blame and shielded his brother Louis. That was typical of Frank Hinkey.

So much for the physical reasons which made Hinkey the gridiron paradox of the ages. The mental angle is even more interesting. "Silent Hinkey," they called him, as befitted so dour, introspective an example of suppressed emotions. Hinkey was an active volcano with the lid clamped on. The lid was off when he stepped onto the gridiron. All the pent up fury of his suppressed energy found expression in those rattling tackles. Hinkey was a genius of the Edgar Allan Poe type. Off the field he was reticent, gruff, preoccupied, quiet - the calm of a summer evening before a storm. When the whistle blew, the Dr. Jekyll in him was metamorphosed into the Mr. Hyde of combat.

Once the game was on, Hinkey became a raging demon, blind to everything but the ball. He played with the supernatural strength of a mad man. Just as an engine has a governor which automatically regulates the expenditure of power so the human organism is equipped with a vast-motor stabilizer that prevents the body from functioning at its full capacity. Under ordinary circumstances, the human motor runs at only 60 or 70 percent of its maximum efficiency. Were it otherwise, we should all "burn up" before our time. The answer to the riddle that was Hinkey lay in his eerie ability to snap the curbing run of his "physical governor," in consequence of which he was able to function at 100 percent efficiency. The brakes were off, literally speaking. Few men can put their "motor governors" out of action at please without losing their reason. Hinkey shared this rare characteristic with Hindoo fakirs, Houdini and other mystics. It is the same untapped force which gives a maniac the strength of four normal men.

Frank Hinkey in action (courtesy of Yale Archives)

There is an action photograph of Hinkey in the Yale archives (see above), which depicts him stalking his man, jowls protruding, teeth clenched, eyes dilated weirdly. It tells better than a thousand words why ordinary courageous rivals made a verbal agreement with Hinkey providing that he should not throw them over his shoulder if they cried "down!" Look at that awe inspiring photograph and you will understand why strong men called "down!" when Hinkey took his death grip. Don't be too quick to call them "yellow." You never faced Frank Hinkey when the battle light shone in his deep set, brooding eyes. Football stars come and go but the only Hinkey has departed the gridiron forever.