Post-yale

Upon graduation Frank stayed in New Haven and unofficially coached the 1895 Yale football team, a common tradition for the ex-captain the previous year. He was accepted into the Yale Law School but instead returned home to 202 Broad St in Tonawanda, NY. The hardware store was struggling to stay afloat. His aging mother was responsible for the daily operations of the firm, along with his two sisters. He also was elected trustee of Tonawanda village on March 16, 1897.

In the evening of August 16, 1897 Frank accomplished something much greater than any gridiron heroics. Eight local residents of North Tonawanda entered a small yacht and began sailing up the Niagara River, just opposite Edgewater (a summer resort) five miles north of the city. A sudden squall swept the river and capsized their yacht, sending the eight men overboard. The waters were too rough to swim ashore, a half mile away, and the men were unable to catch hold of the yacht which was overturned. Fortunately, Frank Hinkey was in a small sailboat and saw the eight men struggling for their lives. With complete disregard for his own safety, Frank jumped into the rough waters and rescued them all.

Frank coached the North Tonawanda High School football team in 1897 to an undefeated season, earning regional honors as the 'Champions of the Northeast'. The Madison High School football team in Madison, Wisconsin claimed to be the 'Champions of the West', going 7-0 without giving up a single point. The Madison people issued a challenge to all comers to play for the U.S. Championship. North Tonawanda accepted this challenge and played America's first High School Football Championship game on Christmas Day in 1897 at Detroit, Michigan. Madison beat North Tonawanda 14-0 under accusations that ringers were used by the Wisconsin team. Several times when Madison had the ball it became necessary to call players out to the sideline and tell them the play signals, which was suspicious given their successful season. Also, the Madison captain often called men by names not written on the official affidavit (roster). When the North Tonawanda players returned from Detroit they were treated to a champions reception by the local community.

Frank continued to help coach the local Tonawanda High School and semi-professional teams (All-Tonawanda) along with the assistance of Louis. In 1899 Frank agreed in principal to head coach the University of Buffalo football team, however both sides were unable to agree upon financial terms. Buffalo had no choice but to play their first game without a coach, eventually hiring Bemus Pierce - star captain of the Carlisle Indian Football teams under Frank's Yale teammates Vance McCormick and Bill Hickok.

Frank Hinkey (on right) sitting on back porch of Grand Island home (circa 1900)

Frank would receive letters every year from subsequent Yale football captains begging for his assistance back in New Haven, which he would graciously provide. Sometimes he would stay for the entire season, primarily coaching end play. Other times the entire team would visit him in Tonawanda. Frank also refereed football contests across the east coast for additional income. One memorable game was the 1903 World Series of Football between Franklin and Watertown. According to Harry March’s Pro Football: Its Ups and Downs, Frank Hinkey was a referee for the event. The referees were dressed in full evening attire, from top hats down to white gloves and leather shoes. During the last play of the game Franklin players, with the game well in hand, agreed to purposely run over the sharply dressed Hinkey, knocking him into the dirt. Frank took the incident in stride and Franklin agreed to pay his cleaning bill. On another occasion, his false reputation for brutality and foul plays resulted in boos from the spectators and after the game Hinkey swore he would never officiate again.

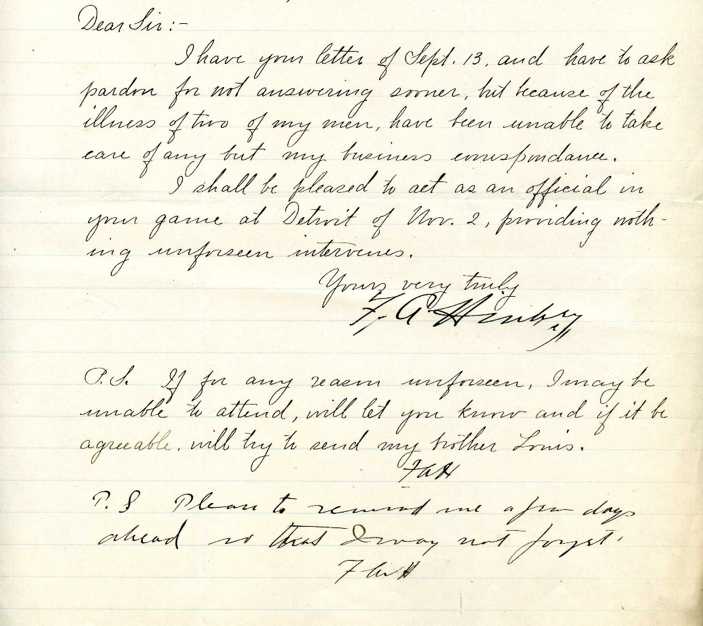

Letter from Frank Hinkey on officiating a football game c 1901 (Hinkey Archive)

Letter from Frank Hinkey on officiating a football game c 1901 (Hinkey Archive)

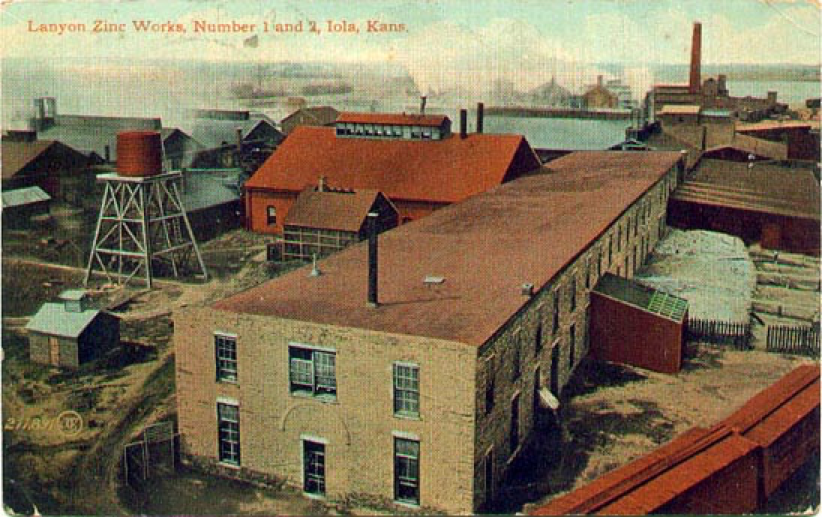

Despite Frank and brother Louis’s best efforts, the hardware store went out of business in 1903. For a couple years Frank Hinkey and Frank Butterworth unsuccessfully sold stocks in New Haven. Responsible for the financial support of his entire family, Frank traveled west to work for fellow Yale graduate and football star James Otis Rodgers at the Zinc Smelting Works of Lanyon Zinc Company in Iola, KS. Zinc is a silvery metal which, combined with copper, is used to make brass. Zinc is also used to galvanize steel (rust prevention). During the early twentieth century zinc was used for buckets, gutters, roofing shingles and lids. The process for smelting zinc required a large amount of coal, so blast furnaces were typically close to coal mines. During the nineteenth and early twentieth century little was known of the long term respiratory complications (chronic bronchitis) from atmospheric work place pollution. Workers exposed to heavy concentrations of coal dust are twice as likely to suffer from chronic bronchitis and disabling lung disease compared to cleaner occupations (all things being equal). Little did Frank know this profession would rapidly shorten his life, given his smoking habit and childhood exposure to tuberculosis.

Lanyon Zinc Works, Iola Kansas (Hinkey Archive)

Lanyon Zinc Works, Iola Kansas (Hinkey Archive)

In 1908 James Rodgers, now president of Lanyon Zinc Works, opened a new zinc smelting plant in Springfield, Illinois. The United Zinc and Chemical Company was located on a 30-acre lot in the far north side of the city near the Chicago & Alton Railroad. The Chicago-Springfield Coal Co provided 100 tons of coal a day to fuel the zinc smelter’s two main furnaces. In 1910 United Zinc increased production from 15-20 tons of finished material to 35-40 tons a day, which forced the employees to work long hours. Given the increased workload, all the zinc workers went on strike. Rodgers needed a proven leader and trusted friend to run this new plant in Springfield. In May of 1910 Frank Hinkey transferred to the Springfield plant as General Manager. The soft-spoken leader squelched the strike within 3 months by negotiating free transportation for his employees to/from the plant. The smelter expanded from 150 to 300 employees and became the most productive zinc smelting plant in the US. In 1913 Frank invented and patented a clean-out apparatus for removing the blue powder (by-product) from the zinc retorts, which revolutionized the smelting process.

In the fall of 1911 Frank met Anna Elizabeth Thomas, the beautiful daughter of Samuel Dayton Thomas. Fifteen years his junior they fell in love and were married on June 12, 1912 at a small ceremony at the Thomas farm in Thomasville (named after Samuel’s father). Roughly 20 local neighbors and family attended the ceremony. When news reached fellow classmate and friend George Sanford on Frank’s engagement he replied “I can’t believe it. Frank would’ve been voted the last guy to get married from our class”. The two resided on the Thomas farm until the fall of 1914, returning to New Haven each fall to help coach the Yale football team.

Frank and Anna Hinkeycouple on left - wedding 1912. (Hinkey Archive)

Frank and Anna Hinkeycouple on left - wedding 1912. (Hinkey Archive)

Anna Elizabeth Hinkey on her wedding day, June 12, 1912 (Hinkey Archive)

Anna Elizabeth Hinkey on her wedding day, June 12, 1912 (Hinkey Archive)

After the 1912 football season, drastic changes were needed at Yale. Yale was the last of the big universities to hire a paid football coach. The so-called “head coach” was almost invariably the captain of the succeeding team, volunteering his time for only room and board. As such, Yale never had the same head coach for two successive seasons. The legendary coach Walter Camp, while head of the Yale athletic advisory council had minimal involvement in direct coaching of the team after 1909, however he had significant influence as chair of the Yale Athletic Association. Under this system of revolving coaches Yale football gradually deteriorated. The 1912 Yale team was considered one of the finest groups Yale ever put on the gridiron but performed like one of the worst over the last 40 years. Captain Hank Ketcham fielded suggestions from Yale alumni and former players, led by Walter Camp, for the 1913 football coach. He created a committee of five graduates to assist with the vetting process. The top three candidates to emerge were Foster Sanford, Howard Jones and Frank Hinkey. Despite a strong endorsement of Frank Hinkey by Walter Camp, Howard Jones was hired as the first paid head football coach for Yale at a salary of $6000/season. While the contract was only for one year it would be renewed annually with the approval of the subsequent Yale captain. Two reasons were cited for hiring Jones over Hinkey – some felt Jones was more familiar with the modern style of football having graduated in 1908. The other was Hinkey’s health was slowly deteriorating over the years and some supporters felt the strain of a long football campaign might be too much for him to bare.

The supporter’s accusations were valid. Frank had a tendency to experience nervous breakdowns, especially regarding Yale football. William Lyon Phelps, a former classmate, stated “After Frank graduated he could never watch a game without becoming seriously sick from nervous excitement. He possessed one of the most peculiar temperaments known of any college man. He told me some years ago that he once waited in New York while Yale was playing Princeton, driving up and down the streets in a taxicab. Finally he purchased a paper, telling of Yale’s victory. At once he became violently sick.” Despite losing out on the head coach position, Frank helped coach the ends that year. The Bulldogs finished the 1913 season in similar disappointing fashion, going 5-2-3 with losses to Harvard and Colgate. Howard Jones resigned at the end of the season to accept a “lucrative business proposition”. A new football philosophy was desperately needed to right the ship at Yale and Frank Hinkey had a radical plan. But was Yale ready for it?

1913 Yale football coaches (L to R) – Hinkey, Bomeisler, Bull, Jones, Vaughan (Hinkey Archive)

1913 Yale football coaches (L to R) – Hinkey, Bomeisler, Bull, Jones, Vaughan (Hinkey Archive)

Head Coach for Yale

On Dec 24, 1913 Captain Nelson Talbott announced Frank Hinkey would be the Yale head coach that season, signing a three-year contract at $5000 a year. Frank arrived in New Haven on Jan 8, 1914 to begin implementation of his revolutionary plan. Yale was going to focus on an open style of play with a heavy emphasis on the forward pass and multiple lateral plays. Up until this time the forward pass, legalized in 1905, was more of a gimmick or trick play. The first passing team in college football was St. Louis University under Eddie Cochem in 1906. Cochems' team compiled an undefeated 11–0 record, led the nation in scoring, and outscored opponents by a combined score of 407 to 11 that year. However this western style of play did not catch on in the east until much later. Unfortunately none of the Yale players knew how to throw the ball. So on Jan 31 Frank brought all interested candidates for the football eleven to the Yale baseball batting cages. He set up targets for each candidates to aim at. They were placed at various distances where he could assess their accuracy. For hours they practiced throwing the ball like a pitcher.

Frank had his work cut out for him. Only three starters were returning from that unsuccessful 1913 season – Captain Talbott, Carroll W. Knowles and Alexander Wilson. Frank brought Dr. Billy Bull onboard to help coach the Yale backfield and provide onsite medical care for the players – the first time Yale had a dedicated team physician.

The first game of the season was against Maine, whom Yale tied 0-0 the year before. With their new explosive offensive attack Yale defeated Maine 20-0. Many felt Hinkey developed the most attractive and original brand of football ever played at Yale. The regular long passes were the first of any eastern college. Eight forward passes were attempted, with six successful.

Their next game against Lehigh demonstrated how quickly the team could score. Outplayed the first two periods, Yale quickly scored three touchdowns to win the contest 20-3. Aleck Wilson, the starting QB, was injured the week before and was unable to play. The 3rd string quarterback led Yale to victory despite Knowles (starting left halfback) suffering two rib fractures. The team was banged up, but their first test was the following week against the all-mighty Notre Dame.

Notre Dame also incorporated the forward pass in 1914 with the assistance of recent graduate and current assistant coach Knute Rockne. Notre Dame came into New Haven riding a 4-year unbeaten streak and were heavy favorites against the Blue. With the steady play of Wilson and Talbott, Yale defeated Notre Dame 28-0. After a disappointing 7-13 loss to Washington & Jefferson, Yale redeemed themselves with a decisive victory against Princeton in the debut of Palmer Stadium by a score of 19-14.

Accolades for Hinkey’s innovative offensive scheme and coaching ability poured in throughout the east. John Field ‘10, Yale 1911 head coach stated, “Frank Hinkey knows more about football than any man in the country. He saw the value of the Canadian passing game, the western open game and eastern air tight defense…and put all these things into his team this year”.

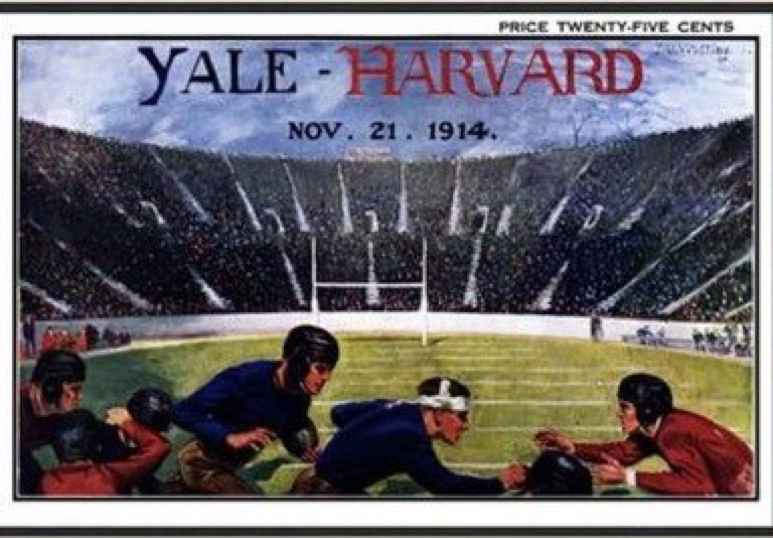

Anticipation for the final game against undefeated Harvard reached historic heights in New Haven. The recently built Yale Bowl, which was the largest athletic stadium in the world, could seat over 70,000. Completed in late 1914 this first bowl-shaped stadium in the country later inspired the design of the Rose Bowl and Michigan Stadium. Tickets for the championship game against Harvard on November 21, 1914 sold out in days. Ex-US presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William H. Taft were two of the many eager to attend. Yale’s explosive offense was favored 5:4 against Harvard’s stifling defense. Old Blue captains and gridiron stars by the dozen lined up at Hotel Taft in New Haven to pass along their best wishes and admiration to Frank Hinkey. Many considered this the best Yale football team in the last five years and the most dynamic ever.

For Yale’s last practice of the season, Frank incorporated the use of a tackling dummy, which he later patented. The newspapers titled the game “Percy Haughton (Harvard coach) against Frank Hinkey” for the 35th contest between the two schools. In front of the largest gathering to ever witness an athletic spectacle in the country, Yale was destroyed by Harvard 36-0. The all-around play of Eddie Mahan and Huntington Hardwick was spectacular. Charles Brickley, the Harvard captain, did not play in the contest due to an operation the week prior. However, to add insult to injury, Brickley came in to kick the last point after the final touchdown under the boisterous cheers of the Harvard faithful.

1914 Yale vs Harvard Football Program (Hinkey Archive)

1914 Yale vs Harvard Football Program (Hinkey Archive)

Harvard turned the dedication ceremonies into the most depressing rout a Yale eleven had suffered at the hands of the Crimson in their forty years of play. Yale’s great hope of a football revival were destroyed on the fresh turf that day. The once overflowing accolades for Frank Hinkey quickly turned to disgust. One Yale alumni wrote “Hinkey’s coaching system should be abolished and Hinkey dispensed immediately”. Prior Yale captains and coaches quickly came to Frank’s defense. This was a strong Yale team which finished 7-2, with their other loss to 10-1 Washington & Jefferson (which also lost to Harvard). They beat 8-1 Virginia, 8-1 Lehigh, 6-2 Notre Dame, 5-2-1 Colgate, 5-2-2 Brown and 5-2-1 Princeton by an average score of 25-5.

Frank was retained by Captain Alexander Wilson for the 1915 football season, however after early warm up losses to Virginia and Washington & Jefferson the captain quickly distanced himself from the head coach. The day after a Colgate defeat by 0-15 captain Wilson stated, “Yale’s poor showing this fall has been due to the fact that the coaching has been done by men without experience in winning elevens”. Similar to his playing days Frank didn’t dispute the accusations or defend himself publicly. Tom Shevlin was brought onboard by Wilson to assist with the coaching. After a close victory against Princeton 13-7, Yale was embarrassed by Harvard in Cambridge by 41-0. After the Harvard victory Shevlin and Hinkey attended the Harvard Club of Boston banquet in honor of their championship team. Both humorously received gold football charms for “contributing much to Harvard’s victory” against Yale. Shevlin joked that Henry Ford would be Yale’s next coach and a telegram from Ford said he promised to get Yale out of the trenches by 1950! Both were good sports and handled the jibes well.

Frank Hinkey was released from his contract at the end of the 1915 season. While the open game is standard play today Frank didn’t have the personnel to effectively run such an innovative scheme. Also, Yale football players were just not the same type of men they used to be. Rather than train hard they waited for coaches to develop shortcuts to success. Upon Frank’s death Walter Camp stated “Frank Hinkey was a superb football man… whose coaching philosophy was ahead of his time”. Despite an abbreviated season in 1917 during WW1, Yale would not have another successful season until 1923 under TAD Jones in his sixth season for the Blue. Frank Hinkey would never assist the Yale eleven again.

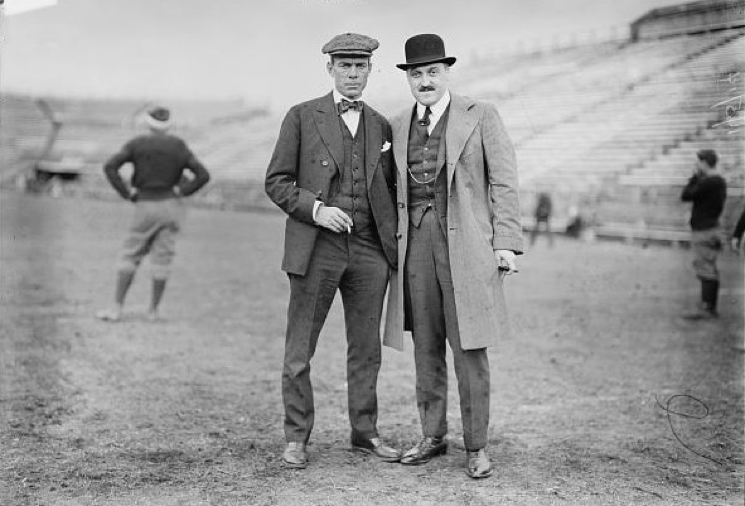

Frank Hinkey and Tom Shevlin circa 1915 (Hinkey Archive)

Frank Hinkey and Tom Shevlin circa 1915 (Hinkey Archive)

After coaching Frank returned to working in the smelting and mining industry. In the spring of 1917 he stayed at the Hotel Luna Villa on Coney Island while he assisted with the construction of a new tin smelting plant. During this period he wrote extensively to his wife Anna, who was back home in Tonawanda with his family. These letters give an in-depth look into the personal feelings and character of an extremely private person. Frank commented “it is ridiculous to have a smelter right in the heart of Coney’s gay doings but they got the power at a fair rate”. He ate most of his meals and spent a good portion of his free time at the Stauch’s Dancing Hall and Restaurant, stating “It is one of the best Coney Island resorts”. Frank also made it known that he didn’t dance but enjoyed watching his friends mingle with the girls. “You should see the young painted short skirted pretty ankled girls do the Fox Trot”.

On April 6, 1917 the United States declared war on Germany, officially entering into World War I. Two weeks later on April 19, there was a “Wake Up America” parade in New York to boost military recruiting. Frank attended that parade and wanted to help the war effort. On May 5th he wrote “I almost feel like a slacker (for not fighting in the war) but good heavens I need to work to support my family and this would be impossible on Army or Navy pay. If I could find someone to take care of the family I think I would try for something”. The “family” were his siblings back home in Tonawanda. After the hardware store went out of business in 1903 and his mother died in 1907 Frank assumed financial responsibility for his family. His two sisters, Mary and Clara, never married and stayed in Tonawanda their entire lives. His brother Louis, was in and out of the Buffalo Mental Sanatorium and never maintained a steady job. Frederick, the oldest, went out west and had little involvement with family affairs. Frank also financially supported Anna’s parents back in Thomasville, who were struggling to pay their mortgage.

On May 16th he wrote “Looks now as though Teddy R would get his wish of taking a division or more of men to France. What do you think of me joining and you get into the Red Cross? I will go to Oyster Bay and see Teddy. I know him years back when he was governor of New York and feel sure he would take me….I would work you in on the Red Cross end. Keep this mum and preserve this letter”. Frank was referring to Theodore Roosevelt’s authorization from Congress to raise four divisions to fight in France. Roosevelt selected a handful of officers to actively recruit volunteers shortly after the US entered WW1. On May 19, 1917 President Wilson rejected Roosevelt’s plan and the volunteer force was subsequently disbanded. While Frank doesn’t mention joining afterwards he continued to frequently comment on the war and how proud he was of the servicemen.

The dominant theme throughout all of Frank’s letters was his unrelenting love and affection for Anna or, as he frequently referred to, “Pal” or “Girl”. Many of the letters discuss financial struggles the Hinkey’s had during this difficult period with frequent mention of stock trading and investment opportunities. However, Frank would ask Anna for approval on every financial decision. Every letter mentions how much he missed her and desired to be with her again. Sometimes, he was a little more direct. On May 10th Frank told Anna “You must be in pretty fine shape by this time being outdoors so much (Anna liked to garden). Fraid I will have to take a run up to see you as I don’t believe I can stand it much longer”. Or on May 24th “Leave for Buffalo tomorrow night, so you better prepare by eating as many raw eggs tomorrow to keep up with me”. Anna never remarried after Frank died in 1925 and spent the remaining 50 years of her life on the family farm in Thomasville, IL until her passing in 1975. They had no children.

Frank Hinkey circa 1917

It was difficult for Frank to find steady work. Frank lived in Dayton, OH from 1920-22 to work at the brokerage firm of DeWeese-Talbott under the service of his 1914 team captain, Nelson Talbott. He also helped coach the 1921 Dayton Triangle Professional Football team with Talbott to an unsuccessful 4-4-1 record. However by this point Frank’s physical condition had rapidly declined. He began to cough more frequently and continued to unintentionally lose weight. Frank and Anna moved back to the Thomas family farm in Thomasville, IL. After spending a year under the care of his wife he entered Pine-Crest Manor in Southern Pines, NC in the spring of 1923. Only two of his closest friends and football teammates, Frank Butterworth and George Adee, knew of his location and medical condition. George Adee commented after Frank’s death in 1925:

“Frank always had been much interested in mythology. It goes without saying also that he was game to the last. Frank Butterworth and I went to Southern Pines to visit him three times last year, the last time being on November 10. When we left Frank, at 8:30 that night, to take a train to New York, Frank pretty well knew it probably was the last time he ever would see us. He was quite visibly affected and tears came into his eyes. He brushed them aside and said: ‘Don’t mind me; you see, they fill me up with cough medicine to stop my coughing. It is all full of dope. It makes your eyes water.’ Frank died at 4:50 am on December 30. He had a premonition two days before that he was going and at 5 pm, on December 29 he sent me a telegram reading: ‘Charon is at the landing.’